The new reintegration landscape, eight years after the Final Peace Agreement signature

Eight years after the 2016 Peace Agreement was signed, the landscape of the reintegration process has changed: 10,265 signatories live outside the Territorial Areas for Training and Reintegration (TATRs), in more than 600 municipalities, whether in towns or cities. Regardless of where they live, most of them remain committed to peace.

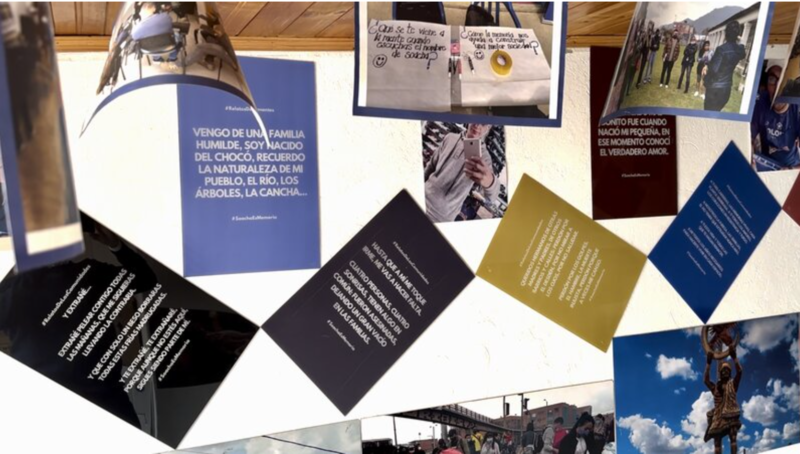

“I come from a humble family, I was born in Chocó, I remember the nature around my town, the river, the trees, the field...”. #SoachaEsMemoria.

Written on a piece of blue colored paper pasted to a white wall, these are the words of Patricio Ramos, a peace signatory from Río Sucio, Chocó. Today he promotes integration between signatories and members of the Soacha community, in Cundinamarca. His message sits alongside dozens of others, written in different colors by some of the over 70 signatories of the 2016 Peace Agreement who live in this municipality, close to Bogotá.

The white wall is in a room that must be about four meters long by two meters wide. There are photographs hanging from a thread that runs from wall to wall and are held up by small hooks. The photos show historic milestones of the Final Peace Agreement, like the signing at the Teatro Colón, but also everyday moments in the reintegration process of former combatants. All the photos were taken by signatories who, individually or collectively, are building peace in their everyday life, in the urban environment - a phenomenon that is changing the reintegration process in the country. The room, the phrases and the photos are part of the foundation “Casa de la Memoria”, an initiative of several peace signatories who began to arrive in Soacha in 2017 from different regions of the country.

Patricio Ramos is the legal representative of this foundation that works to recover and maintain the memory of these years and the efforts to fulfill the Peace Agreement, in a very different setting compared to the traditional spaces that the public identifies as reintegration scenarios. “People think that the signatories who are not in a TATR are getting out of the process, or that we are lazy. What they don't know is that we have had to work harder, we have to pay rent, utilities and fight against stigmatization, because some believe that we come to do harm. But every day we work to fulfill the Peace Agreement, which is a political, ethical and moral commitment”.

Soacha and Urban Reintegration

“Soacha has a particularity,” he adds. “Here there is a large number of victims of the conflict, part of it generated by the same organization (the former FARC), and it turns out that now we are arriving in very similar conditions. Why did we come here? In my case because I had family, but also because Soacha is a large municipality. It has six communes and more than a million people. Here a person moves from one neighborhood to another, and you can't find them,” he explains.

The desire to go unnoticed and feel safe has pushed many signatories, like Patricio, to leave the TATRs. According to the latest report of the UN Verification Mission in Colombia, 10,265 signatories to the Agreement live outside the TATRs - 82% of the total - and half of these, like Patricio, live in urban environments.

Patricio arrived five years ago. Before that, he began his reintegration process in the Brisas TATR, in Carmen del Darién, Chocó, and completed his process of laying down his arms in a new reintegration area, in San José de León, Mutatá, Antioquia. He also tried to live in Río Sucio, on land that belonged to his father, but he says that he was expelled by an armed group. So, he decided to settle in Soacha, in search of security, family and friends.

The first thing he did was to create a clothing business with his sister. When he went to report to the Agency for Reintegration and Normalization (ARN) to continue his reintegration process, he realized he was not the only signatory in Soacha. He met other signatories, such as Olga Bernal, born in Meta, who began her process in the TATR of Icononzo, in Planadas, Tolima, and today leads an association of women for peace. She also met Martha Macana, who founded a food service company.

Community Reintegration

Together, in 2021 they founded “Casa de la Memoria” as a meeting point for signatories, with the support of the ARN’s Program of Territorial Agendas for Community Reintegration and the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

The agendas are part of the ARN’s commitment to promote processes with a restorative approach between peace signatories, communities and institutions. Their purpose is to promote collective actions for the reconstruction of the social fabric and to favor coexistence, reconciliation and non-repetition, elements which contribute to the development of the reintegration process at the community level. This is the objective of Soacha’s “Casa de la Memoria” and of the over 60 other territorial agendas underway throughout the country.

Women in Cali and their experience of urban peace

In Cali, for example, there are 205 people – 53 of them women – taking part in the reintegration process (almost half of the reintegrated population of the entire Valle del Cauca). This city hosts the only Territorial Agenda for Community Reintegration in the country led by and composed exclusively of women in an urban environment. Its history began in March of this year when the ARN asked ten women signatories to put in practice a national initiative seeking to create spaces for dialogue between peace signatories, communities and institutions, with the aim to generate conditions for peaceful coexistence and promote reconciliation.

After several meetings facilitated by the ARN, the signatories decided to convene women leaders and victims of the conflict to foster a pluralistic conversation that could genuinely promote reconciliation opportunities. In May, 20 of these women, many associated with civil society organizations such as the Ruta Pacifica de las Mujeres, Fundación Lila and Fundemixpa, formed a mobilization team and began a dialogue on their needs, proposals and contributions to peacebuilding.

The discussions bore fruit, and the team managed to engage the Cali Mayor's Office and the Governor's Office of Valle del Cauca on the first community proposal that emerged from their talks. Their experience of Comadreo por la Paz was at the core of the festival “Uniendo Voces por la Reconciliación” (Uniting Voices for Reconciliation), which commemorated the International Day of Peace in Cali.

75 new areas of collective reincorporation

Experiences like these are happening all over the country and not only in urban environments, but also in rural areas. Some of them, such as the Soacha experience, are considered collective reintegration spaces, where groups of signatories have begun to build a new life around political, socioeconomic and community processes that respond to their common interests and sense of cohesion. The Mission is monitoring up to 75 of them in the country.

On 14 August 2024, the Government issued the decree 1048, which recognizes all collective territorial realities arising within the reincorporation process, inside and outside the TATRs. The decree introduces the concept of Special Areas of Collective Reintegration (SACRs) and proposes special support for these entities to manage an institutional offer according to their reintegration needs.

The ghost of relocations

In this new landscape, it is important to remember the impact of the relocations of some TATRs. On 20 August, for instance, the peace signatories of the former Miravalle TATR, located in San Vicente del Caguán, moved to a village in the municipality of El Doncello, Caquetá, carrying their belongings on their backs. They had worked for over seven years consolidating their space in that municipality, with tourism and sports projects such as the world-renowned Rowing for Peace that wanted to “exchange rifles for oars”. But they had to relocate due to the degradation of their security conditions in the territory.

Since the signing of the Final Agreement, at least five of these spaces had to relocate: Santa Lucia-Ituango, in Antioquia (2020); La Macarena-Yarí, in Meta (2021); Mesetas, in Meta (2023); Vista Hermosa, in Meta (2023); Miravalle, Caquetá (2024). In a recent hearing, the Special Jurisdiction for Peace stated that some of these relocations should be considered forced displacements. The difficult security conditions in the territories continue to represent the greatest obstacle to reintegration and sustainable peace.

Although the relocations are a source of sadness and frustration among the signatories, the challenges they face have not weakened their resolve. On the contrary, they have opened the door to new opportunities.

Now, in Doncello, for example, the Rowing for Peace team continues training to consolidate essential skills for their competitions and their reintegration process. “We are reorganizing ourselves. We found a river nearby where we train every day (the Guayas River), to prepare for upcoming competitions. We qualified for the Pan-American in Chile, and we are looking for sponsors, because we want to participate in world and national championships,” says Hermides Linares, peace signatory and member of the Rowing for Peace team.

And this is not the only example. In many other cases, the relocations, although they represented a challenge for the reintegration process, opened perspectives and opportunities.

Assignement of land to signatories in Yalí

For example, in Yalí, Antioquia, the National Land Agency handed over the 333-hectare farm of El Viento, in the Jardín district, to 31 peace signatories and their families who currently live in the Carrizal TATR. They will soon have to be moved because their current territory is part of a forest reserve.

“Although at the beginning we presented resistance and did not understand what was going to happen with the arrival of the signatories, (...) now we are fully committed and we are here to accompany these families,” said John Jairo Giraldo, mayor of Yalí, where the signatories of Carrizal will arrive.

For the peace signatories this represents an important change: “It is a new dynamic for us, because we see a gesture of willingness from the national government. It opens a new chapter in the fulfillment of the Peace Agreement and rural reform. Here we have planned cultivation of cocoa, Tahitian lemon and livestock projects, among others,” said Manuel José López, peace signatory of the Carrizal TATR, in Remedios.

Tierra Grata

Although some signatories decided or were forced to leave the TATRs for other reasons, many others remain. To mention a few: Llano Grande, in Antioquia; Agua Bonita, in Caquetá, and Tierra Grata, in Cesar.

Tierra Grata went from being a mountain covered with bushes and abandoned pastures, to a peaceful town, with a housing project counting 80 houses, many of them already built. Tierra Grata is now a recognized village in the municipality of Manaure, where a few days ago the Ministry of Housing approved a project for the construction of a sewerage system presented by the signatories.

In Tierra Grata, the signatories, with support from the government and international cooperation, were able to manage resources for a kindergarten for 25 children, which is operated by the ICBF (Colombian Institute of Family Welfare); an elementary school, with six classrooms built; a health post with two peace signatories trained by the Red Cross, a library and a cultural collective that provides training in art and photography. It also has a restaurant, hardware store, billiards and a clothing workshop, among other productive businesses and projects.

According to Abelardo Caicedo, leader of the signatories in Tierra Grata, three aspects contributed to the success of their reintegration. “First, planning, because we thought of a place for our future; second, housing, because someone who has a house and a family does not want to take up a gun again; and third, training, because there are already 92 high school graduates and five professional career graduates.”

These examples show the commitment and resilience of peace signatories, who despite all the external threats and assassinations (432, as of 26 September), remain firm in their reintegration process. Overall, although each territory tells its own story, they all have something in common: the resilience of the signatories and the commitment of the parties who continue to build on the legacy of the Agreement eight years after it was signed.

The Challenges

Although there are positive examples, both inside and outside the TATRs, reintegration in the country continues to face challenges. According to latest report of the United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia, the main challenges are in the areas of security, land and housing. “Although the number of murders of former combatants decreased (from 25 in the last quarter of 2023 to 16 in the first half of 2024), other forms of violence persist, such as threats and attempted murders,” reads the report, highlighting how security continues to be the greatest threat to the reintegration process.

In terms of housing, the main challenge is the difficulty in accessing subsidies. When it comes to the land issue, since 2023 former combatants have submitted approximately 486 applications to the National Land Agency through the ARN. Of these, 36 have been prioritized.

The new Integral Reintegration Program, recently approved by decree, is expected to strengthen the sustainability of individual and collective processes, so that each signatory committed to peace has their rights recognized. This program includes the four dimensions of integral reintegration: economic, social, political and community reintegration.

Communication team of the UN Verification Mission in Colombia*.

Article written by the Public Information Officers of the UN Verification Mission in Colombia: Camilo Vargas, Elizabeth Yarce, Esteban Vanegas, Héctor Latorre, Jorge Quintero and Nadya González.

UN

UN